So you’re not a perfectionist. Are you sure about that?

Misconceptions about clinical perfectionism and how to turn it into healthy striving.

Dr Hannah Ryan

Perfectionism is not what you think it is. Or, more accurately, perfectionists are not who you think they are. When we think of a perfectionist, we often think of a "Type A" personality: a chef who manages her kitchen with an iron fist, a writer who works at dawn with a furrowed brow, a runner who breaks triathlon records for fun.

As Katherine Morgan Schafler points out in The Perfectionist's Guide to Losing Control, the perfectionist can also be the guy in his pyjamas playing Call of Duty all day who is too debilitated by a fear of failure to try at life. We think of perfectionists as the ones who have everything under control. But he might also be the thirty-year-old rising to the top at work with an overflowing laundry basket and a non-existent dating life. You might think of the perfectionist as the woman who always drops her essay off a day early with a smile and a ponytail- but she might be the one with a healthy work-life balance. The true perfectionist might actually be the one panting through the door two minutes after the deadline with bloodshot eyes and a messy bun saying, "I'm so sorry, please, please, please, can I still submit?". Because she just had to read one more paper, she couldn't not add one more reference before letting it go.

Perfectionists also have a habit of believing that perfectionism is about perfection, and perfection to a perfectionist is always something illusory that exists out there. They often appraise their own output as too mediocre, too short of the mark to qualify as one of the team, not realising that this precise mindset reveals them to be a classic perfectionist with an equally classic lack of self-awareness.

So what is perfectionism anyway?

If perfectionism is not about perfection, what is it about? Let's start with a definition. Roz Shafran, one of the preeminent perfectionism researchers, defines it as "the over-dependence of self-evaluation on the determined pursuit of personally demanding self-imposed standards in at least one highly salient domain despite adverse consequences (Shafran et al., 2002, p. 778).

The most important part of this definition is the over-dependence of self-evaluation on external success, a rather judgmental phrasing, but there you go. According to the CBT model of clinical perfectionism, this is what distinguishes it from "healthy striving" or a "functional pursuit of excellence" (Shafran, Cooper & Fairburn, 2002). In other words, the healthy striver will be discouraged but not feel like they are falling apart if they get a C on their essay or lose the season's biggest match. They will not berate themselves, either. "What matters is the taking part", and "I tried my best", said, um, no perfectionist ever.

Equally noteworthy is that perfectionism can relate to one life domain, several or all. A perfectionist may require a pristine home, but she may be more flexible at work, whilst another may pursue unrelenting standards at the office but have the home of a wild hippy.

What are the other defining characteristics of perfectionism?

Here are some other characteristics shared by some, if not all, perfectionists.

A goal orientation rather than a values orientation. Suppose you want to spot a perfectionist on a date. He is much more likely to say, "I want to be earning 100k by the time I'm thirty" than, "I want to find work that feels fulfilling, be a present father and earn enough money so that I can provide, but I also want balance in life".

Rigid, all-or-nothing thinking and a win-or-lose mentality. There are no prizes for taking part in perfectionism land. The cake either turns out exactly like the recipe (if their perfectionism is generalised or if baking is in the perfectionists' domain of perfection), or you might as well throw it in the bin. You either win the match or you have let your team and supporters down. Your essay either gets a first, or you have "fucked it up" and are probably not going to achieve your goals. Your writing is either exceptional or embarrassingly bad and destined for the delete button. You might as well do the whole thing properly or not start at all. You are either a great mum or a terrible one. By comparison, healthy strivers show more flexibility, self-compassion and tolerance of mistakes.

High levels of self-criticism. Perfectionists have a loud inner critic and a poor tolerance of perceived mistakes. "I tried my best, and I'm proud of myself anyway" is not likely to come out of the mouth of a perfectionist - at least not until after they've been through a process of recovery from perfectionism.

Instead, perfectionists have strict rules of "musts", "shoulds", "nevers", and "always", which boss them around like inner dictators. "I shouldn't have been late, it's completely unacceptable", "I have to get this done by tonight or it will be a complete disaster", "I never get my audit done on time, I'm so unfocused!", "I always make a mess, I'm so lazy and disorganised".

Some cheeky researchers nicknamed these phenomena the "tyranny of the shoulds" (Homey, 1950) and, the psychologists' favourite, "musterbation" (Ellis and Harper, 1961).

Perfectionists often secretly believe that their self-critics are vital motivators and that if they were to fire them, they would become lazy slackers who achieved nothing and would have to resign themselves to a perfectionistic nightmare of slobbery and mediocrity.

Self-evaluation which is disproportionately based on striving and achieving. Almost all of us value striving and achieving our goals, but many perfectionists prioritise productivity, goal acquisition and achievement based on external standards above their internal well-being. In other words, perfectionists live life more from the outside in than the inside out. They would rather sacrifice sleep to perfect that presentation or study for that exam- not just as a once-off, but regularly. Because achievement is more important to a perfectionist than inner peace. Not that they would admit it.

An aversion to rest, balance and meaningful self-care. Many perfectionists use productivity to defend against old memories or difficult feelings; if they rest, they may judge themselves for being lazy or worry that they are at risk of getting in touch with feelings they would rather not feel. As a result, some keep perpetually busy even if they have been warned by doctors to sit still; they flit from one project to the next because if they are not producing and ticking items off their Mary Poppins To Do list that magically manifests more items every time they near the bottom, they feel guilty and rotten in a way they can't put their finger on.

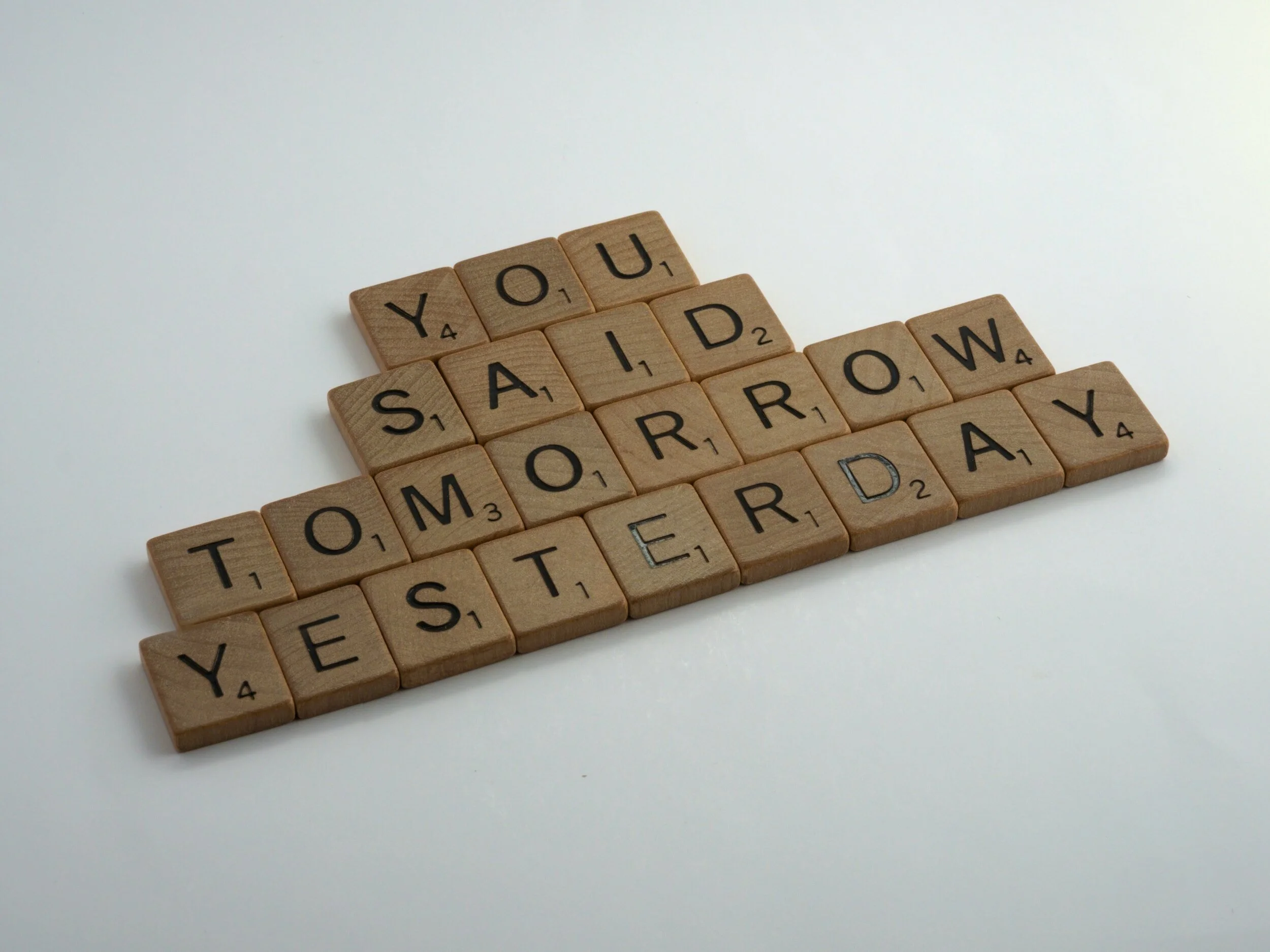

Avoidance and procrastination. Other perfectionists are not actually out there striving. Instead, they are doing anything to avoid failing publicly. These perfectionists may struggle to finish projects because the idea of not excelling is unbearable. However, all perfectionists are generally more prone to procrastination and avoidance than healthy strivers. Let's take perfectionistic writers. Many would prefer to write nothing and preserve the fantasy of an alternate universe in which they have several perfect books which are not only adored but critically acclaimed and adapted into tasteful films than have to face the excruciating possibility that they might not be the Booker nominee they’d dreamed they might be.

The belief that perfectionism is really about excellence. Most perfectionists struggle to see their perfectionism clearly. They often hold tightly to the idea that their perfectionism has served them well, and they are usually at least partially right. We live in a world in which perfectionists get better grades, more praise from teachers, and better jobs - until, of course, they burn out, drop out and start having panic attacks or paralysing depressive mood swings and need lots of support to get back to a functioning baseline. But persuading perfectionists to let go of their grip on the part of themselves that has undeniably brought success, approval, status, social leverage and prosperity is never easy- even if it has caused undeniable harm to their mental health.

Low self-esteem or fluctuating self-esteem?

Perfectionists may not only often fail to recognise their own perfectionism, they may also be fooled into believing they have no issues with self-esteem. This is because the concept of low self-esteem may not resonate with a perfectionist. The term implies a stable low opinion of oneself; it conjures up a stereotype of a shrinking violet in the corner pulling their cardigan sleeves over their hands. This is unlikely to fit every perfectionist, as they come in all shapes and sizes. A perfectionist is equally likely to be the guy on the table funnelling beer into people's mouths, not realising that if everyone stops paying him attention, he will have to sit with the unbearable weight of his feelings.

Regardless of the exterior, for the perfectionist, esteem is usually a volatile energy whose stability depends not on solid ground but on their perfectionistic domain's unpredictable success or failure. Consider an appearance-related adolescent perfectionist. Perhaps she received harsh parenting at home and cruel bullying as a child, but as an adolescent, the world began rewarding her for her looks. After a diligent contouring session, she receives 380 likes on her Instagram picture and hundreds of "stunning" compliments. In this moment, she may indeed feel elevated to the status of stunning. With a rush of adrenalin, she may even feel emboldened to send a provocative photo to her crush. Is this someone who needs more confidence? Surely not! Wrong, because all it will take is one unflattering photograph uploaded by her frenemy for her self-esteem to tumble painfully down; she will feel instantly hideous, disgusting and undesirable and want to dive under the duvet and hide in shame for perpetuity.

Where does perfectionism come from?

"To believe that you must earn love through perfectionism, or that you must seek love from others in order to become whole, turns us all into hungry beggars" - Elizabeth Gilbert

Many routes lead to the development of perfectionism, both inside and outside the family home. However, they have in common that the child is left with a deep, intangible sense that something is fundamentally wrong with them. The language of deficit has gone out of fashion for good reason in psychology, but bear with me. A developing perfectionist may acquire a developmental injury in their sense of self; perhaps they develop the core belief that "I am bad" or "I am unloveable". This can then go one of two ways: either they try to be perfect at everything, to conceal their perceived core badness or unlovability with a sort of scattergun perfectionistic approach, or they latch onto a specific domain in which they have been manifestly praised and rewarded for being inherently excellent such that this becomes their primary identity.

Perhaps they are a rugby prodigy, and they are told, "You are a phenomenal sportsman with a bright future", both explicitly as well as implicitly through the cheers, the claps on the back, the sense of belonging, the admiration and the dopamine-inducing attention from attractive girls. Winnicott's true self/false self theory may be helpful here. In this example, the identity of the "popular rugby player" becomes the false, idealised self, propping up the teenager's fragile self-esteem with a feeling of specialness that compensates for lack of feeling good enough deep down; in reality, the foundations of his selfhood are shaky at best; he is only ever as "good" as his last score, and while he can oscillate between elated and okay as long as his sportsmanship is burning bright, a career-ruining injury could easily send him into a deep depression which only meaningful therapeutic work would likely unravel.

This is what perfectionism really looks like.

And our culture has a lot to answer for. If you panicked when you read any of the above, don't. Because the likelihood that we will all emerge from childhood feeling robustly good enough is, through my anecdotal observation as a therapist and human, not at all high. Not only is developmental injury common but our cultures also glamorise achievement with a borderline obsession. Let's not forget that we live in a world where celebrities were recently put behind bars for paying hundreds of thousands of dollars for someone to photoshop their children into Ivy League universities. And we can't just point and laugh at the Americans. The culture of prioritising achievement over well-being is ubiquitous; it permeates our schools, social media accounts and our homes; it spans East and West, and it has never been more prescient than for the current generation.

That's why Katherine Morgan Schafler threw a "trying really hard" party when she had written half her book on perfectionism to model a different set of values to her daughter. She said:

"What's considered "normal" to celebrate in our culture is based on culture's priorities, not our own priorities. We celebrate promotions, winning, best-seller lists, speed (30 under 30), balloons that spell out "1 million followers!" Nothing's wrong with celebrating any of that stuff. What's not great is when something's important to you, and it's not celebrated. Celebration is a signal to yourself and the universe: this matters to me, this is a big deal, this is worthy of acknowledgement, pause, cake!"

But, you might be asking, is perfectionism really a bad thing?

No, and yes. Maybe. It can be. Here's why.

It can be counterproductive and make it harder to achieve your goals.

It makes you far more prone to avoidance and procrastination.

It can cause harm to your relationships, as it encourages you to prioritise achievement and status over connection.

It can cause harm to your relationships in other ways, because you might project your perfectionism on other people, requiring them to conform to your high standards and becoming critical, irritable or hurtful if they do not.

It significantly increases your vulnerability to mental health difficulties- and we have the research to prove it.

If we were to plot perfectionism on a graph, we could think about its relationship with productivity on a bell curve. In small doses, perfectionism might ramp up your drive and focus. However, as it takes over, it can erode your mental health, compromise your connections, increase your vulnerability to anxiety, depression and decision paralysis and interfere with your ability to build and sustain a happy, rich, meaningful, connected and balanced life. Considering this, it might be worth reigning it in, don't you think?

So, how do we keep our perfectionism within healthy limits?

Here's how in a nutshell:

Recognise that your perfectionism is a helpful part of you when it is influencing but not controlling you. Learn to ask your perfectionistic part to take a step back. When it is in the driver's seat, it may go on a rampage through your life. We don't want to get rid of it, but we don't want it to have so much power any more.

Develop a values orientation alongside a goal-orientation. Learn to learn into other domains outside of achievement. This will look different for everyone but might include nurturing relationships, making time for play and creativity, giving back, creating for fun or learning for the sake of it, among myriad other possibilities.

Cultivate self-compassion. Self-criticism and perfectionism go together like birds of a feather. Self-kindness and perfectionism are like oil and water. Give yourself permission to be good enough. Give yourself permission to rest. Give yourself permission to be human. Celebrate having baked the cake even though it was a little burned. Celebrate having showered even though you were grieving or depressed. Celebrate having worked even though you were exhausted. Celebrate having been kind even though you were irritated. Celebrate having cleaned half the kitchen. Celebrate trying, even if the outcome wasn’t award-winning. What would that be like?

Make friends with vulnerability. Brene Brown has much to say about this and has said it far better than I ever could.

Prioritise rest and nurturing your inner self alongside striving. Whole books could be written on this, and indeed many have been. However, most people's avoidance of rest runs deep. Bring this one to therapy; you might be unable to work through the blocks alone.

Overcome avoidance and procrastination. This is connected to all of the above.

Cultivate self-compassion. Oops, I said that already. See, perfectionists? I made a mistake in this article and survived! Only joking; I just thought it was worth repeating…

The good news is that finding a healthy balance is possible, and many therapeutic approaches can cleverly, compassionately and effectively help. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Compassion Focused Therapy, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Internal Family Systems Therapy can all reduce our dependence on our protective perfectionistic parts and help us develop resources to shore up our sense of being good enough.

Can perfectionism ever become a good thing?

Perfectionism can become a benign or even benevolent force once you have built a new relationship with its more destructive behaviours. Healthy perfectionists in recovery learn to embrace rest and meaningful self-care, know how to be profoundly kind and supportive towards themselves, are forgiving and tolerant of their own (and others) mistakes, nurture and prioritise their values, live life from the inside out more than from the outside in, set realistic, flexible goals, celebrate small wins, take baby steps for the sake of it, and learn to switch their perfectionism on and off as needed. With the proper support and resources, you can learn to do this, too. You certainly have the determination to get there.

The bottom line.

While you may be more of a perfectionist than you previously thought, this isn't something you need to be ashamed of. In our culture, many of us will likely emerge from childhood with more than a few perfectionistic scratches, but these can be moulded into a mark of strength. Acceptance and Commitment Therapists tend not to pathologise any trait as "all bad" or "all good"; instead, we consider its meaning in context. Rigid perfectionism, with its death drive towards achievement and productivity at all costs, is invariably harmful to the host. But recovering from this tendency can transform perfectionism into your superpower, as the kids say. Perfectionists in recovery tend to be willing to go the extra mile for excellence, pay more attention to detail, and persist when the going gets tough. And, let's be honest, sometimes it pays dividends to read that email through an extra couple of times…

For resources to help you tame your perfectionist drive, check out the list below.

Thoughts for Reflection

Were there any parts of this article that resonated with you? If so, what were they?

When you think of your perfectionistic parts - or those parts of you that are driven to work really hard, try really hard and impress other people- can you think of a person or people in your life from whom you learned this way of being?

What were some of the implicit (unspoken) messages in your family, school or culture that made it clear that rest would be disapproved of and that certain types of productivity and achievement would be rewarded?

When you feel you need to take a sick day for something ambiguous (e.g. you are feeling “off”, fatigued or run down - but it’s not clear cut) are you able to advocate for yourself and take this sick day? Or do you push your body beyond its limits? Do you often find yourself feeling guilty if you let yourself rest and feel it’s neither justified, earned or deserved?

If you identify as a perfectionist, in what ways have your perfectionistic parts helped you in your life? How have they supported you to get to where you are? Would you like to thank them and extend them gratitude for their hard work?

What percentage would you like your perfectionist parts to take a step back? How much would you need them to step back and create some space in order for you to take a breath and nourish yourself?

If you would like to move away from perfectionism towards a healthier relationship with yourself, can you think of any role models in your life? Do you know anyone you admire who seems to unapologetically allow themselves to rest, play and pursue joy for themselves? Do you know anyone who allows themselves to be good enough rather than overworking themselves into perfection? Do you judge this person, envy them or admire them?

As you reflect on your relationship with productivity, perfectionism and rest, what is one message you would like to take away from this article? How could you keep this message alive in your life in the coming weeks and months, if you wish to, and what difference would it make to your wellbeing if you could?

Videos, books and Podcasts for Perfectionists in Recovery.

Videos

Brown, Brene. TED TAlk. The Power of Vulnerability. Brené Brown: The power of vulnerability | TED Talk

Chen, Daryl. TED Talk. Self-worth theory: the key to overcoming procrastination. Tired of procrastinating? To overcome it, take the time to understand it | (ted.com)

CBT for perfectionism self-guided self-help video by iCope. Online Workshops - iCope

Books

Shafran, R. Overcoming Perfectionism, Second Edition. Overcoming Perfectionism, 2nd Edition: A Self-Help Guide Using Scientifically Supported Cognitive Behavioural Techniques (Audio Download): Roz Shafran, Sarah Egan, Tracey Wade, Amy Lyddon, Steph Bower, Hachette Audio UK: Amazon.co.uk: Audible Books & Originals

Brown, B. The Gifts of Imperfection. The Gifts of Imperfection (Audio Download): Brené Brown, Brené Brown, Penguin Audio UK: Amazon.co.uk: Books

Morgan Schafler, Katherine. The Perfectionists’ Guide to Losing Control. The Perfectionist's Guide to Losing Control (Audio Download): Katherine Morgan Schafler, Katherine Morgan Schafler, Orion Spring: Amazon.co.uk: Books

Podcast Episodes

230. The Laziness Lie with Devon Price – Psychologists Off the Clock (offtheclockpsych.com)

88. Perfectionism with Sharon Martin – Psychologists Off the Clock (offtheclockpsych.com)

Podcasts

How to Fail with Elizabeth Day How To Fail With Elizabeth Day on Apple Podcasts

Unlocking Us with Brene Brown: Unlocking Us - Brené Brown (brenebrown.com)

The Imperfects. The Imperfects on Apple Podcasts